Flying business class on British Air was definitely a good decision, as they have seats that become completely flat, allowing reasonable quality sleep on the way to London. The business class lounge at Heathrow was rather crowded, but less so than the terminal in general. And they have free internet access. I kept myself awake during the London to Accra flight, in hopes of adjusting my body to the time zone change. By the way, Ghana is pretty much on the Prime Meridian, so just a five hour difference from the east coast of the U.S..

The immigration and customs formalities were surprisingly quick and straightforward. While waiting for my bag, I changed money. The exchange rate is roughly1 U.S. dollar = 9000 Ghanaian cedis. Since the largest note is 20000 cedis, you inevitably end up with a remarkably thick wad of bills. By the way, "cedi" is pronounced like "CD" and I could make a bad pun about it being a rather seedy currency. I should also note that the cedi may be on the way out. No, the replacement is not called the deeveedi, but the Anglophone countries of ECOWAS (the Economic Community of West African States) are going to have a common currency called the "eco." I saw lots of billboards advertising the "eco" but was unable to figure out what stage of deployment it's in. The one store I was in that had actual price tags did have them labeled with both the "c" for cedi and "e" for eco, but I never saw an eco.

My bag showed up and I exited the terminal. There were a few touts, but it was really pretty low-key for a major Third World transit hub. I found the Tusker sign and met Eddie, as well as our local guide, Paul. Eventually, the five other people from the group who'd been on the same flight showed up and we headed off to the Novotel for the night.

All in all, our group included 14 paying customers, Eddie and Amy (Eddie's wife), Martin, and Paul, plus a support staff which even included a cook. (Our cook prepared lunch, using the facilities of whatever cafe or bar we stopped at, while the hotels we stayed at provided dinner and breakfast. Breakfasts were generally eggs and/or cereal, while lunches and dinners typically had salads, pasta, bread, and chicken or fish or both.We almost always had pineapple, which we decided was the official dessert of Africa.) Five of the group had been on Eddie's eclipse tour in Australia in 2001 and a few others were eclipse groupies, with one couple having seen four. I will continue my general policy of not commenting publicly on fellow tourists, beyond noting that we got along generally well as a group.

After a brief orientation in the morning, we boarded our (air-conditioned) bus and were off through the traffic of Accra. We passed the National Theatre, an elegant modern building built by the Chinese in 1992, and Independence Square, which features an arch with a black star, symbolizing African independence. We also passed a lot of street hawkers, offering everything from bags of fried yams to newspapers to toilet paper to something called "miraculous chalk," which turns out to be an insecticide. The hawkers are somewhat controversial. Many of them are young people trying to raise enough money to open up conventional stores. Apparently, there are some elements in the government who consider the large number of hawkers to be an indictment of their economic policies. And, of course, the informal economy doesn't lend itself easily to tax collection. But it seemed to me that a lot of Ghanaians like the convenience of not having to go to stores to purchase their daily necessities.

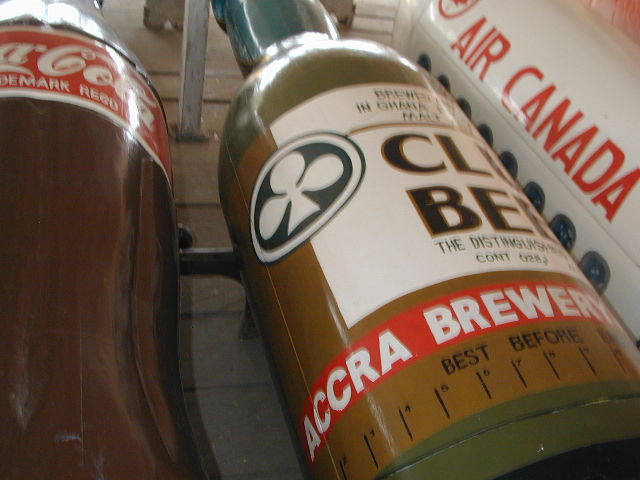

We continued on to our first stop - the coffin makers. This sounded very odd to me when I saw it on the itinerary, but Ghanaian coffins are fascinating. They're made in fantasy shapes, which people specify in their wills. For example, there are coffins shaped as fish or airplanes or shoes or crabs, or even bottles of beer. I've known people who wanted to be buried in beer bottles, too, but most of them were trying to do it while they were alive.

By the way, a fantasy coffin costs roughly 6 million cedi, versus the 500,000 to 1 million for an ordinary coffin. So they are decidedly a luxury item. Still, people are dying to get them. (Come on, you knew I couldn't resist a bad joke like that.)

We went to two coffin stores before we returned to the center of town and went to the National Museum. I should mention something about Ghanaian business names first, though. A large number of the businesses we saw had names that incorporated religious slogans. For example, I noted "Anointed Hair Care," "Hands of G-d Engineering," "Blood of Jesus Bicycle Tires," and "If G-d Wills It Battery Reconditioning Service." We saw similar slogans on the back windows of taxicabs, too. This practice was so widespread that I didn't even bother trying to write them down after the first day.

The museum is a good and comprehensive one. We had a museum guide, with supplementary comments by Paul. Paul started out talking about Ghanaian names, which have to do with the day of the week on which a person is born. So, for example, U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan was born on Friday. From now on, when I listen to Kojo Nnamdi on the radio, I'll always be reminded that he was born on Monday.

One of the key exhibits at the museum is on textiles. Bark cloth is made by pounding the bark from trees. Then there's adinkra, worn for funerals, which is in black and dark red and block printed. The blocks for the printing are cut out of calabashes. Finally, the most famous Ghanaian cloth is kente, which is woven in strips. There's a bit of a rivalry between the Asante and the Ewe as to who invented kente. Paul, who is Ewe, insists that the word comes from the Ewe for "open, press" to prove the precedence.

That isn't the only subject of tribal rivalry, apparently. We continued through other museum exhibits, e.g. musical instruments, slavery, archaeology (which includes items from elsewhere in Africa, including Egypt). At the one on puberty rites, somebody asked about circumcision. The museum guide said that men in most tribes are circumcised. The Asante circumsise, but the Asantehene (the king of the Asante) is not That led Paul to say that the Asantehene is more important than the president of Ghana, provoking outrage from the museum guide, who shouted "I am Ewe. The Asantehene is nothing to me."

After having lunch at the museum cafe (prepared by our cook, as I noted above), we drove through past the grand Parliament building and Supreme Court. Almost immediately we entered the old shanty town part of Accra, Jamestown. We continued on a long drive to Elmina. Paul talked about Ghanaian history, but bus trips often make me doze, so about all I absorbed was that the Portuguese, Dutch, German, and British colonized Ghana, in that order. We spent the night at the elegant but sprawling Elmina Beach Resort, where we had dinner and the first of our nightly astronomy talks.

The next day's sightseeing started with St. George's Castle. This is the oldest colonial building in sub-Saharan Africa, having originally been constructed in 1482. I gather, however, that it was modified quite a bit over the years.

Just below the castle, there's a lively fishing harbor, full of colorful pirogues.

Paul warned us not to give our names to the children who swarmed us when we got out of the bus at the castle. Apparently, their trick is to write your name on a seashell and insist that you buy it. We shook them off without too much difficulty and entered the castle. Our first stop there was the original Portuguese church, which is now an entirely unmemorable museum. The rest of the castle was considerably more interesting. We started with the dungeons for female slaves, surprisingly small given that they housed 150 women. The women weren't chained, but were fed sparingly to keep them weak. When the Dutch governor wanted to rape a woman, all of them were paraded outside for him to make his choice. The chosen victim was then led up to a trap door to his quarters.

We next went down a narrow tunnel to the gate of no return, where the slaves were led to the ships. We continued on to the condemned prisoner's cell, used for soldiers who had misbehaved. Then came the death cell, where prisoners were starved to death, being given no food or water. That was used for the leaders of slave uprisings, for example. The dungeons for the male slaves held 300 men, who were kept chained.

The top of the castle had an expansive view over Elmina and the Atlantic ocean.

The top level also has the Dutch Reformed Church. From there, we went through the Dutch governor's quarters, which were striking for having more room for one man than for hundreds of slaves. As we left, there was another museum area, whith pictures about the development of tourism in Elmina, and an art gallery with paintings for sale.

After touring the castle, we walked over the nearby fish market. There's a fee to go into the enclosed market area, which is bustling and colorful.

Back on the bus, we continued past posuban shrines. These have some sort of symbolic function, being used for ceremonies. But, oddly, they look pretty much like nicer than usual houses, with figures of people outside.

Our next stop was at what is arguably the most famous tourist attraction in Ghana. Kakum National Park has a rainforest canopy walk which is unique to Africa. It was built by Canadians in 1995 and consists of seven rope bridges, roughly 120 feet above the ground. There are platforms built around the large trees that connect the bridges. The idea is that you're above the rain forest canopy, offering a unique view. The hike up to the start of the walk involves an exposed rocky path, followed by a cooler walk through the forest. It would actually be pleasant to walk more through the forest, but the canopy walk draws a huge crowd and there really isn't time.

Being very scared of heights, I was skeptical of the whole experience. Fortunately, you go one at a time across the bridges - or you're supposed to. The bridges have a solid wooden board with a metal support underneath and the rope mesh comes up to mid-chest height. So it's not as bad as it might be, but still scary. By the third bridge, it was a bit easier, but the end of the fourth seemed to sway a lot. It wasn't until the fifth bridge that I discovered the problem. Two German men were right on my heels, going fast and bouncing the bridge. At the next platform, I let them go ahead of me and the last two bridges weren't so bad. If you think, though, that I was going to let go of the ropes to take a photo, you don't know me at all. (One of the other people from our group did get my picture coming off the final bridge, and I hope he'll send it to me eventually.)

By the way, the walk back down to the visitor center was physically the toughest part of the experience. I guess my knees are weaker than my lungs. Still, it's fine if you take it slow. We had a picnic lunch and mingled with a large group of school children before reboarding our bus for the roughly four hour drive to Kumasi.

In Kumasi, we stayed at the Hotel Georgia, which was just adequate. I had a nice shower, but my roommate was all soaped up when the water shut down, apparently overwhelmed by all of us trying to use it at once. We continued the evening routine of dinner, followed by astronomy talk.

Our sightseeing in Kumasi began with shopping at an antique store. There were textiles, masks, carvings, and stools from all over West Africa. The only item that really interested me was a piece of bark cloth, but it was too large and I decided against the purchase. Others in the group did lots of shopping, however.

We continued on to the Manhiya Palace Museum. The palace is the seat of the Asantehene. The current Asantehene, Osei Tutu II, created the museum in the area that was lived in by two kings, Prempreh I and Prempreh II. Prempreh I was exiled to the Seychelles by the British from 1896-1924 and build the palace on his return. Most of the exhibits consist of photos of royal families, effigies of past and present royalty and chairs or stools used by them. A handful of talking drums and palanquins used to carry the king were somewhat more interesting. But the most interesting thing is that the king still borrows ceremonial objects from the museum for ritual occassions.

We drove past the sprawling market area and stopped at the National Cultural Center, where we ate lunch. That was followed by some free time, which most people used primarily for shopping. I did do some browsing and bought a sort of fabric basket. But I also went to the small museum on the grounds (the Prempreh II Jubilee Museum), which was not vastly different from the Palace Museum. I found a few items particularly interesting, though. There was a collection of linguist sticks, which are used by the king's spokesmen to show their authority. They portrayed the seven Asante clans. All but one clan marry only outside the clan, while members of the crow clan can marry either others within the clan or outside. By the way, clans are matrilineal, as is the royal line. There was also a fascinating war drum with leopard skin trim. This is played with a scraper and the resulting sound is like a leopard's roar. I also found a book of Ananse stories to add to my folklore collection, though I suspect they've been modified to teach children good behavior.

The main event of the day - and a definite highlight of the tour - was attending an Asante funeral. When I had seen the itinerary, I wondered how they knew there would be a funeral to go to. It turns out that Asante funerals are held some time after the person is buried and that there are several on any given weekend. We had a local guide, Peter, who had located a good funeral for us to go to. Paul had already briefed us on how to behave. For example, we were not to wear white. We entered in a single file, men first, followed by women, and walked around, shaking everyone's hands. After making the rounds, we were seated, and people entering shook our hands, too.

The most striking thing about the funeral was the traditional attire worn for it. It is astonishing how many variants there are of black on black fabric, mixed in with red worn by the family of the deceased.

There was also a lot of drumming and dancing.

A woman announced donations to the family. Paul had donated 30,000 cedi on our behalf, and the family came over to thank us for the gift. A big deal was a group of women in black skirts and white blouses carrying gifts on their heads and followed by a boy leading a ram. Paul explained that these are gifts from the daughter-in-law. I was mildly amused that one of the gifts consisted of several cans of soft drinks. It was also notable when a chief entered, with his entourage carrying a large umbrella over his head.

The deceased had been a bank officer and one of the founders of the National Patriotic Party, which is currently in power, so was quite a prominent man. Which was why the real excitement came. There was an announcement that the President of Ghana was coming. Police entered, followed by a motorcade. President John Kufuor got out and made the round of attendees, shaking hands. So, yes, I got to shake hands with the President of Ghana and his entourage. It was very impressive how well liked he is, with people calling out "We love you" to him. It would be hard to imagine an American president in similar circumstances.

In the morning, we left Kumasi for the long drive to Akosombo. On the way, we stopped at Lake Bosumtwi, the largest natural fresh-water lake in Ghana. We took a cruise around the lake in a shaky wooden motorboat. The lake is sacred to the Asante and it is said that the souls of the departed visitit on their trip to eternity. Our local guide told an origin story for the lake, involving an unsuccessful hunt. The hunter's wife saw an antelope jump in the lake and disappear, so they knew the lake was sacred. There are small villages around the lake and lots of fish nets strung in the water. Our boatman had to stop a few times to free the rudder from the nets, in fact.

We continued on to an Asante traditional house, which I believe was the shrine house at Besease. This was a four-sided thatch-roofed structure, decorated with adinkra symbols cut into the clay. I can't say I got much more out of it, but it was attractive. That was followed by a long drive to Akosombo. Along the way, we passed one market where there were giant snails for sale. Eventually, we arrived at the Senchie Riverside Resort on the Volta River. This was a lovely setting - at least until the power failed, cutting off the air conditioning. While they fixed the problem, several of us retreated to the bar, next to the river. By the time we'd had dinner and the evening lecture, the air conditioning was back on and we could sleep comfortably.

The next morning took us to the town of Krobo Odumase and Cedi's Garden Bead Company. We got a tour of the entire bead making process. Old beads or glass bottles are ground into a powder. Some bigger glass pieces are melted together to make translucent beads. The powdered glass may also have pigment added to it. Developing a patterned bead is similar to laying down a sand painting. The molds are put into a kiln at 800-1000 degrees Celsius. They're removed using a device rather like the paddles used to take pizzas out of ovens and annealed by being cooled ina box of sand. Sand and water are also used for polishing. There was also a studio where Venetian style beads are made from glass rods.

Of course, there was plenty of time for shopping. It's amazing how inexpensive many of the beads are. The finest ones, though, go for 200,000 cedis and I saw a few I liked, one of which I did purchase. I also bought some beads and buttons to use in embellishing knitting projects.

After everyone was done shopping, there was a performance by a dance troupe. There was an interpreter who explained the stories behind the dances. For example, one involved a bride being trained to take care of her husband.

My favorite dance was one where they were weeding in the garden and a snake came along. The snake was a little stick being pulled on a string and it was all quite clever. But the real highlight was just taking pictures of the colorfully dressed people.

We had lunch in the middle of the dancing and then reboarded the bus to drive to Ho. Once we settled into Chances Hotel, we had an opportunity to go into town. I thought I'd look for n internet cafe, but wasn't successful at that. So I just meandered around the market area, which is typical of the sort, before joining the others who'd come along for a beer at a local bar.

The next morning started with a visit to the small Ho Museum. The textiles, including various kente patterns, are one of the major exhibits. There was also an interesting exhibit on twins, who are considered sacred. If a twin dies, the surviving twin carries around and cares for a doll to represent it.

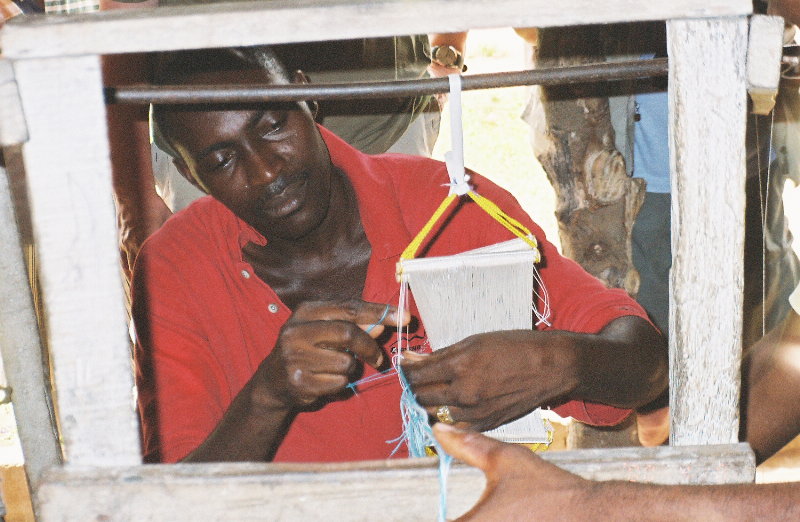

We continued on to a village where kente is woven. The entire process was demonstrated, from winding yarn onto bobbins, to warping the looms, to the actual weaving. The loom is foot-operated, requiring bare feet to work the mechanism to open the threads. Overall, the process is not really any different from any other weaving process, except for the heddle being made of threads, rather than a rigid frame.

There was, inevitably, shopping time and the sellers were very aggressive. There were some nice large pieces, but I don't have room for them. I finally settled on a couple of long strips, intended to be used as scarves.

We walked over to the next village where we met the soothsayer. He's an elderly man, perhaps in his 90's, and he told us about the last eclipse in 1947. The story was that they sacrificed two chickens and, when they ate one, it was bitter. We were also told bout a person who looked at the eclipse through a coke bottle and was blinded. One of our group had her fortune told, a process involving cowrie shells being shaken in a box. I won't violate her privacy, but will note that she had been skeptical, but was very pleased with the results.

After having lunch (back at the first village), we returned to the hotel. Some people went into town, but I decided I needed a nap, a shower, and the hotel's internet cafe, not necessarily in that order. In the early evening, we had a briefing about the eclipse viewing the next day. Eddie explained how he and Paul found the site we'd go to and persuaded the local villagers to let us use it. The negotiations involved having to drink large tumblers of schnapps with the chief. The agreement included the villagers clearing a path to the top of the hill and setting up a shelter for us. There was also a brief discussion of eye protection. The eclipse chat was followed by dinner. Since we'd have a very early morning departure, there was no lecture that evening.

The other mornings had all been at least somewhat overcast, so were were concerned about the weather. Fortunately, my faith in my weather karma proved justified and eclipse morning was crystal clear. We left at 6:30 a.m. and drove about a half hour to the eclipse venue. The path had, indeed, been cleared and the climb to the top of the hill was easy enough. At the top, there was a makeshift shelter covered with fresh palm leaves and a bunch of plastic chairs. There was also a wonderfully panoramic view.

By the way, a number of the villagers also came to watch. We had a bit of a wait to first contact, at 8:02 a.m.. Eddie handed out eclipse shades and everybody arranged whatever viewing equipment and camera gear they'd brought. I had decided not to attmept photographing the eclipse because I wanted to focus on the experience and not be distracted by the demands of the camera. What I did have (in addition to the shades) was a solar viewer from Rainbow Symphony, who also, by the way, manufactured the shades. This glass filter provided an excellent undistorted view. Another person had a simple but effective solution - welder's glass duct taped over the front of binoculars, providing a magnfied (and green-tinted) view.

One interesting effect came about 15 minutes before totality. The palm fronts of the shelter act as pinhole cameras, projecting crescents onto any available surface. This otherwise silly photo of a chair is pretty cool once you know what effect is being captured..

I'd been wandering out to look and then returning to the shelter off and on, but about ten minutes before totality, I settled down to watch steadily. The sky was getting darker and the air cooled as the crescent got thinner and thinner. Finally, there was just a slice, which gradually dissolved to a bead shape before vanishing altogether. At totality, it is safe to view without protection and the sight is, indeed, awesome. There were lots of shouts of glee at the beauty. All in all, I feel privileged to have been able to have seen the eclipse.

We were told when to resume using eye protection and watched a bit of the sun's return before descending the hill. We boarded the bus and went on to the nearby village of Abutia Tete. The villagers welcomed us eagerly, to say the least. One woman danced around, waving a cloth and shouting "welcome, welcome, welcome."

Each of us had beads fixed on our wrists and got numerous hugs. We also had to pour a little water from a bowl onto the ground. Then we were led into the village square where the people put on a bobobo dance for us. Paul said this is the origin of the Brazilian samba. The music is certainly lively and we all joined in the dancing until we were told to take our seats for the entrance of the chief. Then came the usual greeting ceremonies at any village. You squat while greetings are exchanged. The chief's spokesman pours libations for the spirits and you also explain the purpose of your visit. We were each given a copy of the chief's business card, showing his job title as "The Paramount Chief of the Aboutia Traditional Area." That certainly sounds more impressive than my own "Senior Project Engineer" but my company won't let me put "Paramount Evil Genius" on my business cards. Finally, we were given palm wine to taste. Most of us didn't manage more than a taste of it, but we noticed that our leftovers were gulped down by one or two of the villagers.

The greetings were followed by more dancing and lots of photo opportunities. All in all, it was quite a party.

After eating lunch (somewhat uncomfortable with the villagers watching us, but Paul said that was what they wanted) we went on the bus to see the local hospital. There was a woman giving birth at the maternity hospital, but the midwife came out briefly and spoke with us. Then we walked over to the clinic and met with a man who said he is the "prescriber." I suspect he is something like a physician's assistant or maybe a nurse practitioner. For anything requiring inpatient care (or, for that matter, an actual doctor), people neeed to go to Ho. They have few supplies. For example, patients have to buy their own syringes and even latex gloves. The most common problem, by far, is malaria, with tuberculosis also a significant concern. Several people asked about sending help and Paul said that it's best to do so via the chief.

We returned to the village and entered the chief's compound for a "family photo," with all of us gathered around the chief and elders. Then we went back to Ho. A few people went to town, while the rest of us just relaxed at the hotel. Before dinner we went around the table, with each person talking about the highlights of the trip. What was striking is that, while the eclipse was an obvious highlight, everyone had truly enjoyed the variety of things we'd done in Ghana.

Most of the group returned to Accra in the morning. One couple were going to stay in a village, which has an interesting and unusual Jewish community. And I was off to Togo and Benin. But that's another chapter, so read on.

[ Back to Index | On to Next Chapter ]

last updated 15 April 2006